Common Mistakes Beginners Make in Circuit Building

Getting into electronics is exciting, but nearly everyone hits the same painful bugs at the start: circuits that “should work” but don’t, random resets, and burned LEDs. Most of these problems come from a handful of simple mistakes that are very easy to avoid once you know what to look for. Understanding them early will save you time, money, and a lot of frustration.

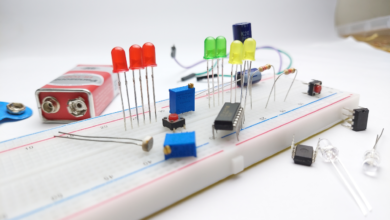

Misunderstanding the breadboard

One of the most common beginner issues is not really knowing how a breadboard is connected internally. Power rails often run along the sides, while the middle area is grouped in short rows, and some boards even split the rails in the middle. If you assume “every hole in a column is the same,” it is very easy to put two legs of a component in the same node and short it, or to think two points are connected when they are not.

Beginners also tend to build with long, crossing jumpers that hide which rows are actually linked. This makes both wiring mistakes and debugging more likely. The cure is simple: learn the breadboard layout once, use short colour coded wires, and double‑check each connection against the schematic before powering up.

Power and polarity problems

Power mistakes are responsible for a huge share of dead components. A very typical error is reversing the battery or mixing up VCC and GND on a module, which can instantly destroy ICs or electrolytic capacitors. Another is using “whatever adapter is lying around” without reading the label, feeding 12 V into a 5 V circuit or exceeding the current rating.

Even if the voltage is correct, running motors, LEDs, and logic through the same thin jumper wires can cause big voltage drops and random resets. Good habits here include: always checking the adapter voltage and polarity, measuring rails with a multimeter before connecting sensitive parts, using current‑limiting resistors on LEDs, and giving motors or high‑current loads their own thicker supply paths.

Guessing instead of reading datasheets

Many beginners wire parts purely by copying diagrams or guessing, without ever opening a datasheet. That leads to things like driving LEDs directly from a 9 V battery, choosing random resistor values, or powering 3.3 V sensors from 5 V “because it worked in one tutorial.” These circuits may function briefly, but they are unreliable and often shorten component life.

Datasheets look intimidating, but for most parts you only need a few key lines: allowed supply voltage, maximum current per pin, recommended operating current, and maybe a basic application circuit. With that, you can do quick Ohm’s‑law checks—like calculating the right series resistor for an LED or confirming a regulator can handle your load. Treat the datasheet as your friend, not a last resort.

Building everything at once

Another classic beginner mistake is assembling an entire project microcontroller, sensors, display, motors, communication modules and then powering it for the first time. When it inevitably fails, there are too many potential fault points to know where to start. You can’t easily tell if the problem is wiring, code, power, or a bad component.

Experienced builders work in stages. First they bring up just the power supply and verify the voltage. Then they test the microcontroller alone with a “blink” sketch or serial print. Next they add one sensor or module at a time and confirm each works before proceeding. If something breaks, it almost has to be in the bit you just added, which makes debugging much easier.

Skipping systematic debugging

When circuits misbehave, beginners often start moving random wires, swapping components at random, or rewriting big chunks of code without a plan. That can hide the original fault and create new ones, making the situation worse. Others rely only on whether an LED lights instead of using a meter or logic probe to see what is really happening.

A more effective approach is deliberate and calm: start with a visual inspection for reversed parts, misplaced jumpers, and shorted pins. Then verify power rails with a multimeter, checking both voltage and continuity. After that, follow the schematic from input to output, measuring a few key nodes and comparing them with what you expect theoretically. Change just one thing at a time and note the result. Every bug you track down this way teaches you something about real world behavior that no textbook alone can give.

By watching out for these five areas, breadboard wiring, power and polarity, ignoring datasheets, building everything in one shot, and unsystematic debugging… you will move from “my circuits never work” to “I can usually make them work” much faster. Those early mistakes are normal, but you do not have to repeat them once you recognize the patterns.

This is all about Common Mistakes Beginners Make in Circuit Building, Thanks for reading.

Check out my other articles.